The two Philip Stacks of Coolkeragh in County Kerry, Ireland lived side-by-side for most of their lives, but examining the land records and their death registrations makes clear that in life as in death, there was disparity between Irish farmers and agricultural laborers.

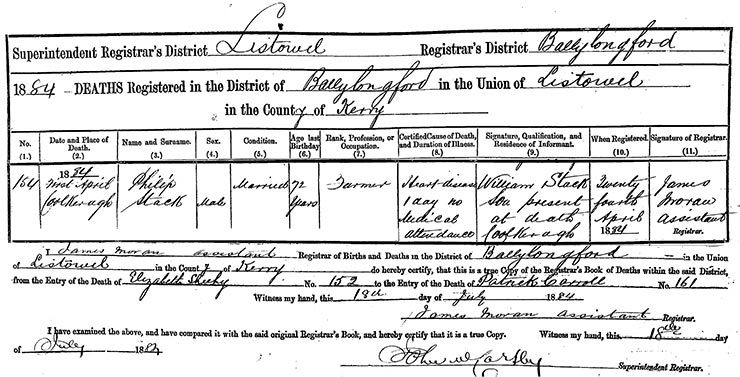

My great great great grandfather, Philip Stack the farmer, died in April, 1884, and his death record reads: Philip Stack of Coolkeragh, aged 72, married, died of heart disease. His son William Stack was listed as present at the death, and Philip’s profession was given as a farmer.

Philip’s widow Mary Moloney lived until June of 1899. Her death record notes her as dying in Coolkeragh, a farmer’s widow, because even as a widow, the distinction mattered. The witness was Kate Collins, daughter, who was present at the death.

Philip Stack the farmer and the later generations of his family had some measure of security through the land that passed through the generations. After Philip’s death the lease was transferred to his son William, who later emigrated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania around 1890. In 1900, the lease was then officially transferred to his sister, Catherine (Kate) Collins née Stack, who was then Philip’s only child who remained in Ireland.

Kate had been widowed with two toddlers in 1875, and later managed to buy the family house and land outright through the Land Purchase Act of 1903, which gave tenants government assistance in buying the land they farmed, and represented a huge transfer of wealth back to the local Irish population. It was, of course, the farmers who were able to take advantage of the program, while most laborers were left behind.

And what of Philip Stack the laborer? In 1887, during the Kerry “Land Wars” that led to the Land Purchase Act, most of the residents of Coolkeragh were issued evictions. Ireland was in a depression, the price that farmers could get for produce had dropped, yet their rents remained impractically high.1 As a result, tenants were unable to pay their rents, and some (often absentee) landlords responded by foreclosing and evicting them, often en masse. Coolkeragh was in the hands of George Sandes, one of the most hated land agents in all of Ireland. He was infamous for, among other things, raising rents whenever a farmer passed his lease down to a newly married son, or if the farmer showed any signs of prosperity, such as his wife or daughters being dressed well.2

In April of 1887, four families were evicted, and then in June, 41 eviction notices for Coolkeragh were published in the Kerry Sentinel, including that of Philip Stack the laborer. Based on how many families were evicted, it appears that the entire townland received eviction notices, farmer and laborer alike. In some cases, evictions encouraged tenants to pay off their debts to their landlords. In others, they lost their leases but were let back in as at-will tenants or as caretakers.

“A tenant evicted and then readmitted as a caretaker or tenant at will lost his status as a tenant under the Land Act of 1870: he lost, that is, his security of tenure,” J.L. Hammond wrote in Gladstone and the Irish Nation, “All then that a landlord had to do in order to extinguish customary and legal rights was to evict his tenant and take him back as caretaker.”3

The Land Valuation Office records for Coolkeragh show that most of the tenants managed to stay on their properties although the records do not make clear on what terms. Philip Stack the laborer may have been allowed to remain on his small plot of land as a caretaker, because local land records suggested that he stayed in Coolkeragh until 1899.

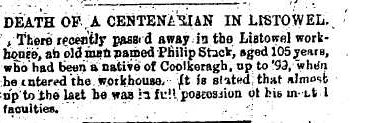

Then, in the December 19, 1903 edition of the Kerry Evening Post, a small notice appeared:

“DEATH OF A CENTENARIAN IN LISTOWEL. There recently passed away in the Listowel workhouse, an old man named Philip Stack, aged 105 years, who had been a native of Coolkeragh, up to ‘99 when he entered the workhouse. It is stated that almost up to the last he was in full possession of his intact facilities.”

The actual death record says that Philip Stack was a 92-year-old widower (the newspaper likely embellished his age) who died in the Listowel workhouse of senility “2 years certified” on December 13th, 1903. Philip’s profession was given as a laborer, and it was signed by Daniel J. Hickie, occupier of the Listowel Workhouse.

Workhouses, like the one in Listowel, were a place of last resort for the poverty stricken in Ireland. The elderly and infirm could end up in the workhouse if there was no one at home to care for them, as could orphans, unwed mothers, the indigent, and others who had no family or enough money for their upkeep. During the Great Famine (1845-1852) there were also able-bodied people in the workhouse who were too poor to feed themselves, but in the years after the famine, including when Philip Stack was an inmate, “out-relief” or welfare benefits were available to the poor, so the majority of workhouse inmates were those whose families just couldn’t, or wouldn’t, take care of them.

Although Philip was listed as a widower in the 1903 death record, his wife Johanna, née Tennant, was found on the 1901 census in Listowel, the closest urban center to Coolkeragh. She lived on Bridewell Lane, so named for the notorious gaol there.4 At the time of the census there were 44 families, including the Stacks, living in 19 homes on Bridewell Lane.

In 1892 The Irish Peasant drew an alarming picture of the life of laborers forced to live in the “village” rather than on the farm. “Their lot is a wretched one, living in a cabin in a village street. This hovel is ill-kept, ill-drained, with a roof of rotten thatch, from which the green ooze drains down the walls. These men have no land, no pig, no poultry. They have miserable wages and everything must be bought. Everything means some potatoes, a little bad bread, stuff called tea, and perhaps a bit of coarse, American bacon on Sundays.”

The family’s crowded living arrangements were recorded in the census. Philip’s wife Johanna stayed with their daughter Mary and her husband Robert Jones and their nine children. Johanna shared a room with her bachelor son John Stack, and another room was occupied by a widow and her adult daughter. It seems little wonder that with 16 people in a run-down, crowded cabin with little sustenance, they felt unequipped to care for the aging Philip Stack, who ended up spending his final years in the Listowel Workhouse.

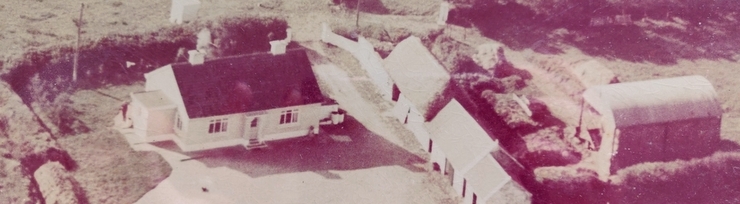

Even after their deaths, the respective statuses of each Philip Stack continued to resonate. Farmers had the opportunity to accumulate generational wealth, and pass these opportunities on to their children, even if that simply meant buying them a ticket to America. Philip Stack the farmer was able to pass his lease on to his wife and children after his death. All of his children except one emigrated to Pittsburgh and leveraged their familial relationships to launch themselves into the American middle class, including my great-great-grandmother. The daughter who stayed, Kate Collins, eventually bought the family property outright and it stayed the family for subsequent generations. In the 1960s Philip’s great-grandchildren received an inheritance from one of their Stack uncles in America and added a new house to the property with all the “modern conveniences.”5

The other Philip Stack’s children were bound by the same constraints as their father. They were laborers, too. They moved to the cities and lived in cramped houses in crowded streets until they disappeared or emigrated. Because they were landless, their history was far more difficult to trace. It’s possible that Philip Stack the laborer’s descendants went on to become successful Americans like the descendants of their neighbors, but if they did, it was certainly a far more difficult journey.

Esmonde, Thomas. “Tenant Farmers (Ireland)- Evictions From Inability to Pay Rent.” House of Commons Debate, 25 August 1886, UK Parliament. Commons and Lords Hansard, vol 308 cc486-529. ↩

He was also known for sexually assaulting the young wives and daughters of his tenants, and workhouse inmates. MacMahon, Bryan. The Great Famine in Tralee and North Kerry. Dublin, Ireland, Mercier Press, 2017. Chapter 8, “George Sandes’ Visits to the Workhouse.”

“Ireland As It Is: VII. In Kerry.” Flag of Ireland [Dublin, Ireland], Vol VI, No 259, 22 Aug. 1886, p. 2

George Sandes’ name comes up repeatedly in the collection of folklore collected by Irish schoolchildren in the 1930s. One such tale was collected by Tomás Ó Báiréad: “George Sands went into a farmer’s house one time as he had the habit of doing so. The young girl of the house was ironing a white petticoat for the races. ‘Oh miss – that petticoat is good enough for my wife’, said George and he put a rise of ten pounds in her fathers rent after.” The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0406, Page 132, by Dúchas National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin ↩

Hammond, J. L. Gladstone and the Irish Nation. 1st ed., Routledge Revivals, 2019. ↩

Butler, Richard. “‘A Scene of Shameful Disorder and Dissipation.’” History Ireland, vol. 28, no. 2, 2020, pp. 26–29. JSTOR, Accessed 2 May 2021. ↩

Undated letter from Catherine A.V. Lyons, granddaughter of Philip Stack, quoting her cousin after a visit to Coolkeragh, Ireland. ↩