“That a bright young man, honored by a fine position, favored with excellent health, and with an exceptional bright future before him, should meet death at his own hands seemed a direct contradiction of what should be.”

The Inter Lake, Kalispell, Montana. January 6th 1893

I first came across Charles Duer McCreary while researching one of his half siblings, and the sparseness of information about him made me curious. A handful of online family trees listed him, based on a single source, the 1880 census, when he was 13 years old. There was no information about what became of him. Intrigued, I decided to try to flesh out his biography. It took some digging, but eventually I located dozens of primary sources.

Here is the story I discovered. It shows that a great deal of information can be unearthed about someone who lived more than a century ago, but also that there are some questions about a person’s life, or death, for which the historical record may not be able to provide any answers.

A Civil War family

Life didn’t turn out very well for either of the Charles Duer McCrearys. The first, buried in Cockeysville, Maryland, died before he was a year old. The second, saddled with the name of his dead brother and the responsibility to outlive him, managed to do so, but only by 24 years. The second Charles Duer McCreary was found in Montana, on the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, 1892, dead by a self-inflicted gunshot at the age of 25.

Charles was the son of William G. McCreary, a 30-year-old physician, and his second wife, Rebecca Norris Duer, a spinster from a well-regarded Maryland family. William, recently widowed with three young children, enlisted with a Pennsylvania regiment at the start of the Civil War, and soon after began his brief courtship with Rebecca. At age 33 and with an unmarried older sister to serve as a warning, Rebecca may have been eager to marry, even if it meant taking charge of William’s three children while he was away at war.

The couple went on to have three children of their own. The first Charles Duer McCreary was born on November 8, 1863. By then his father William was a captain in the Signal Corps, and in April 1864 he requested a leave of absence of at least 20 days to “attend to affairs of such a delicate nature at home that unless compelled by the necessity of such leave I am unwilling to place a public application.”2 3 It appears that his request was granted, but not until a year later.

By that time the son he had never met was dead, but during his time off he conceived a child with Rebecca. William mustered out in August 1865, and returned home to Washington, D.C., where a daughter, May, was born in 1866 and the second Charles Duer McCreary arrived on February 28, 1867. Charles, like his brother before him, were named after Rebecca’s father, Charles Duer.

Early years

On December 12, 1869, when Charles was just two-and-a-half, his father died in Washington, D.C. The cause of death was recorded as injuries that William had sustained during a war-time train accident. It appears that the family may have been in financial difficulty even before William’s death; the doctor who attended to him in his final illness, R.S.L. Walsh, didn’t charge the family for his services, later stating, “Dr. McCreary having been a physician and his family poor, no account was kept of visits made or services rendered.”4

From the collection of Ron Seidlich.5

After her husband’s death, Rebecca was granted custody of Charles’ three elder half-siblings from his father’s first marriage. But just six months later they were living with their mother’s family in Pennsylvania, while Rebecca, supposedly their guardian, was in Baltimore.

On the 1880 census Charles was living with his mother and older sister May in Fallston, Harford County, Maryland, where Rebecca’s mother’s family were from and where several of her Duer siblings had settled. That year he competed in a corn-growing contest, which was written up in a local newspaper. All of the other boys competing were listed, with their names, ages, and parents’ names. Charles was recorded as, “Chas. D. McCreary, 13, Father dead.”6

By the time Charles was 18, his mother was in ill health and was becoming progressively worse. The family was living on the Civil War widow’s payments Rebecca was receiving, and a bequest her childless uncle, David Lee Norris, had left for her in his will in 1893. Rebecca’s bequest was more substantial than that of his other nieces and nephews, presumably because her position as a bedridden widowed mother was more precarious.

And what of Charles? With his mother in decline, he may have felt pressure to make his fortune and provide for his mother and sister. Or perhaps he wanted to get away from the stifling atmosphere of living with an ailing mother and an older sister, an environment that would have been difficult for any teenage boy.

Luckily for him, three of his aunts and uncles had already left Maryland for the Montana Territory, which was fast on its way to statehood. The frontier had ample opportunities for ambitious young men, especially ones as well connected as Charles.

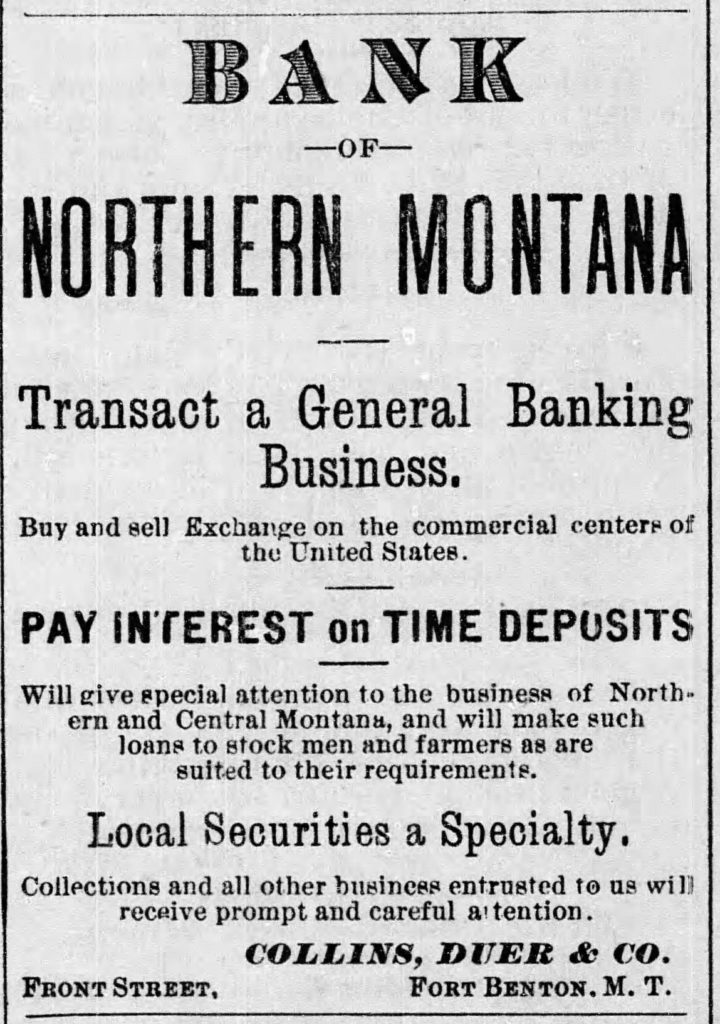

His uncle, Charles E. Duer, was a founder of the private banking outfit Collins, Duer, and Co. and the Bank of Northern Montana, which provided banking services for ranchers and farmers taking advantage of the territory’s abundant public-domain grasslands. Mr. Duer was well regarded in Montana and was considered “a serious minded, intelligent business man, having the confidence of all who knew him.”7

Life in Montana Territory

On April 1, 1885, an article in The River Press in Fort Benton hailed the arrival of a stagecoach carrying Mr. and Mrs. Charles E. Duer, who were returning from a holiday, and announced that they were accompanied by Mr. Duer’s nephew, Mr. Charles D. McCreary.

Charles, just 18 when he arrived in Montana, immediately began to work for his uncle at the Bank of Northern Montana in Fort Benton, learning the banking trade and, according to newspaper reports, “gaining a host of warm friends in the city.” 9

What would a young man like Charles have made of Montana? He had spent most of his childhood in and around Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, both historic, developed cities. Now he found himself on the frontier, where immigrants from Europe were pouring in, the native population was being displaced, and opportunities for young white men to make their fortunes abounded. Montana must have felt novel and exciting, a world away from life in Harford County.

But all was not well at home in Maryland. A local newspaper, The Aegis & Intelligencer, published regular updates on his mother Rebecca’s health. In October of that year her illness had worsened and her physician, Dr. Gorsuch, considered her condition very critical. Two months later she was no better, and was described as being in a “precarious state of health.”10 By the summer of 1886 Dr. Gorsuch had declared her an invalid.

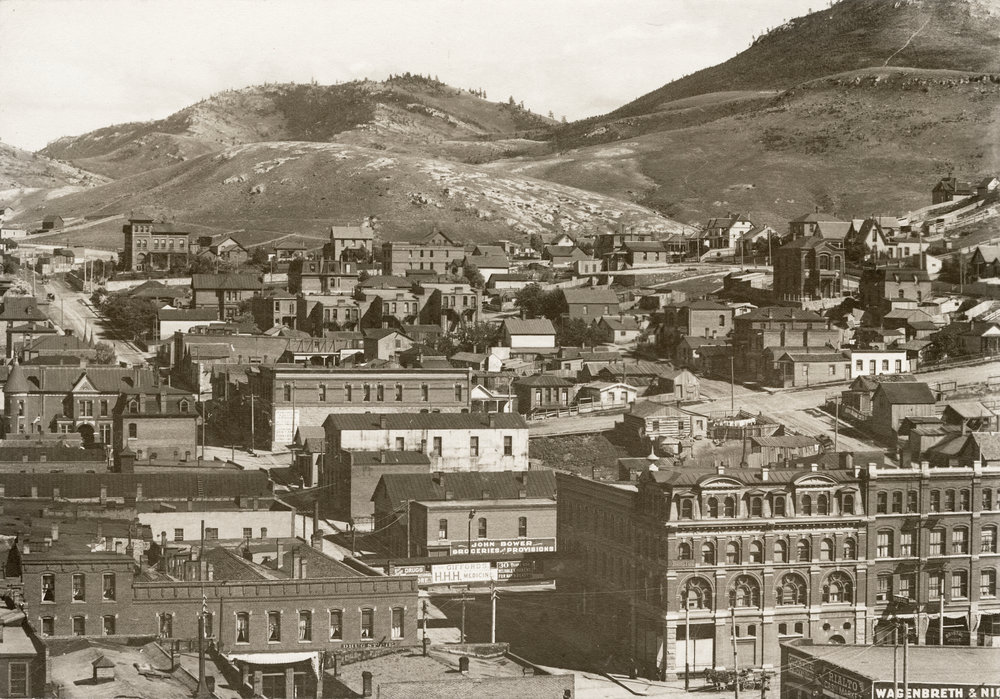

Far from his mother in Montana Territory, young Charles seemed to find his footing during this time. After keeping the books for his uncle’s Bank of Northern Montana for a year and a half, he accepted a job at the Merchants National Bank and relocated to Helena, about 150 miles southwest in October 1886. Helena, “Montana’s Paris,” was many times the size of Fort Benton, and was considered to be, “without question, the metropolis of the Territory.”12

While the River Press in Fort Benton reported “Charley’s departure will be regretted by many friends,” the local papers in Helena were only too happy to have him, and he began regularly appearing in the society notes of the newspapers there.13

On October 13, 1887, he attended the 15th wedding anniversary of Mr. and Mrs. James P. Porter, where he presented the happy couple with a crystal water jug for which he had clubbed together with two other young men. In March 1888 in Helena he was “overheard” talking about what a fine new building the Merchants National Bank would erect that summer.

Helena society life

In early 1889 Charles participated in a flurry of parties and social events. He “made the rounds” in society on New Year’s Day, and then two days later attended a dance put on by the Pioneer Club, a social organization known for its regular soirees and hops. A few weeks after that he attended a musical at the home of the territorial governor of Montana, Preston H. Leslie. Back in Fort Benton he attended a “progressive Euchre party,” where he won the booby prize, a small wooden scoop embossed with gilt letters that spelled out “scooped” along the handle.

A few days later he received sad news, a telegram informing him of the death of his mother. “Mrs. McCreary was a widowed sister of Mr. Chas. E. Duer, of this city,” a Fort Benton newspaper reported. “She had been an invalid for years, and her death was a relief from suffering that medical skill could not alleviate.” 14

His mother’s will left everything to her two children, Charles and May. To Charles she left a dozen silver-plated forks, one dozen tea knives, half a dozen tablespoons, one pair salt spoons, and one teaspoon, which at the time were valued at less than $20. His sister May received the rest, half immediately and half in trust to be held for her benefit. The inventory of the will records his mother’s estate as being worth $1,350, most of it in Baltimore City stock that she had received from her uncle. The inventory included a “sick chair” but did not list any cutlery, silver or otherwise.

Was such an uneven distribution between her two children only because May, who had nursed her mother tirelessly through her infirmity, and was yet unmarried, had more need of a nest egg? Or was it a slight against Charles, who had left just as his mother became ill?

Charles may have been confused, but he did not mourn his mother’s death alone; his mother’s two sisters, Susan Duer and Phoebe Duer Moffitt, also lived in Helena.

Charles, who was then 21, went on with his life and his social engagements in the Montana Territory. A few months after his mother’s death he joined the Helena Tennis Club and was elected to the Membership Committee of the Republican Club. As a bachelor, he did not have a permanent residence, and during this period lived in a boarding house at 213 Broadway in Helena, where meals were cooked by the proprietress. Later he boarded at the Brunswick Hotel.

The end of 1889 brought celebrations and events as Montana was granted statehood in November. Under the headline “STATEHOOD AT LAST” the Helena Daily Herald wrote, “As fine a day as ever an autumn sun shone upon ushered in Statehood in the capital of Montana.” After receiving the news by wire from Washington, the Herald quickly spread the world around town and reported that the news “passed from mouth to mouth quickly and in a few moments every man who chanced to meet a friend on the streets was shaking hands with him over the joyful tidings, while many a ‘smile’ was taken in popular resorts in honor of the occasion.” 16

Helena, the capital of the new state, had gone from a dusty gold-mining camp to the “Queen of the Rockies,” a city awash in wealth. It was said (perhaps with some exaggeration) to be home to more millionaires per capita than any other city in the world.

In December there was an all-day Silver Jubilee for Bishop Brondel, of the Helena Catholic diocese, celebrating the 25th anniversary of his ordination. After evening services at the cathedral the Bishop held a reception at his residence, in which the “parlors, corridors, and dining room were handsomely decorated with natural flowers.” Several hundred ladies and gentlemen came to pay their respects, including Charles (although he himself was a Presbyterian), and were entertained with music by the St. Ignatius brass band, “composed of Indian boys.”18

Starting over in Kalispell

Throughout his time in Montana Charles faithfully corresponded with his sister May, who remained in Maryland. On September 15, 1890, there was a notice of a letter for Charles waiting at the Missoula Post Office. There was another notice on January 29, 1891, of a letter for him at the Helena Post Office, and another on May 13 of the same year of a letter waiting for him at the Fort Benton Post Office. It seemed that Charles was traveling around the state, or that his friends and family didn’t know where to find him. Around this time he landed in the newly created town of Kalispell.

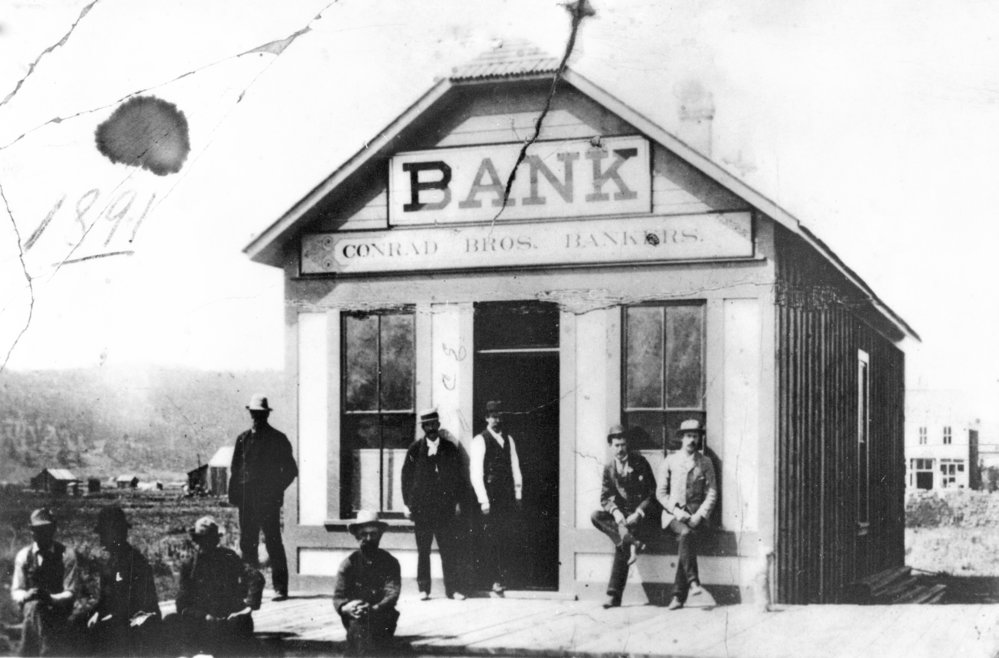

In 1891, in northwest Montana, the town of Kalispell was born as a joint venture between the Great Northern Railway and banker Charles E. Conrad. At the time the land was almost entirely undeveloped, but Conrad immediately started flogging properties to new settlers, and the Great Northern Railway made the fledgling town its only stop in Flathead County, snubbing nearby Demersville, which was known as a place where “rowdies frequently took perch atop storefronts and drunks teetered at the roofline.”20

A new town bankrolled by Conrad Bank, already being flooded with investors, would have presented a golden opportunity for Charles, who now had several years of experience as a banker in Montana under his belt. The Conrad Bank was started in a “one-room frame shack on the corner of First and Main streets” in Kalispell in May 1891 and opened to the public the following month with Charles D. McCreary as the assistant cashier.21

The summer of 1891, Kalispell’s first, “saw the establishment of 23 saloons, half a dozen gambling joints and a like number of honkey-tonks, two Chinese laundries and the same number of Chinese restaurants, and four general stores.”23

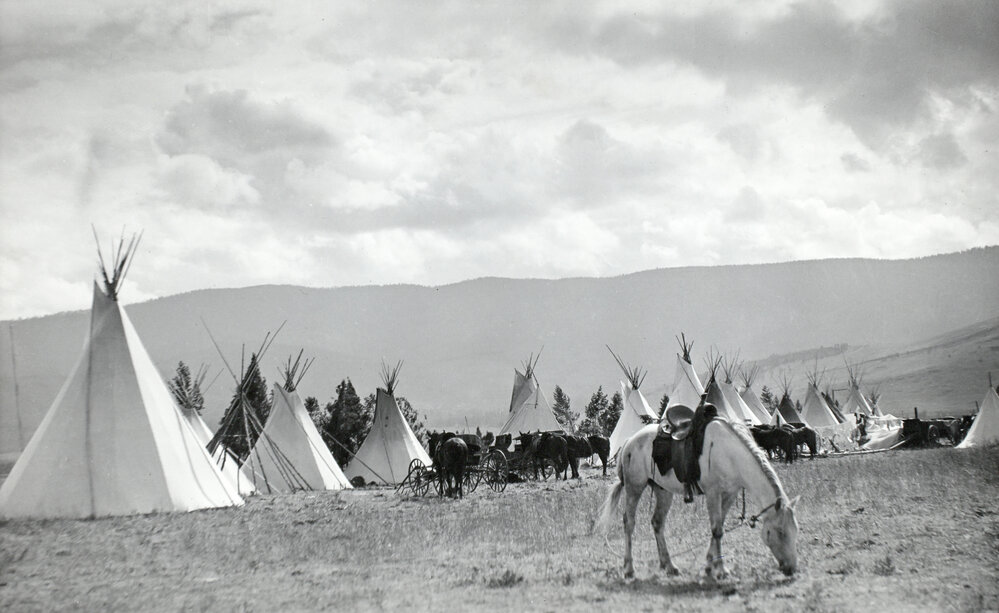

Although the tribes of the Flathead Valley had been pushed into a reservation to the south of Kalispell, many still lived independently outside of town and would visit, unsettling the new pioneers. The town’s first chief of police recalled that the Kutenai people “from who we had filched the valley, were very much about.” 24

And indeed the newspapers were filled with news about Indian attacks and accounts of kidnappings of local children (which were later admitted to be untrue). At night the new residents of the town could hear the chanting and drums of the Kutenais as they rhythmically beat on dry cottonwood logs outside of town. During the day the townspeople sold the Kutenais liquor and were cursed at in both Kutenai and English.

Charles was an active member of the fledgling frontier town, which had a population of around 2,000, with more arriving every day. He helped organize Kalispell’s first volunteer fire department, where he held the position of secretary. He was a founding member and financier of the Ancient Order of United Workmen, a fraternal organization that offered accident insurance, burial benefits, and the like. He rounded out his busy schedule as the treasurer of the Blaine Republican Club of Kalispell.

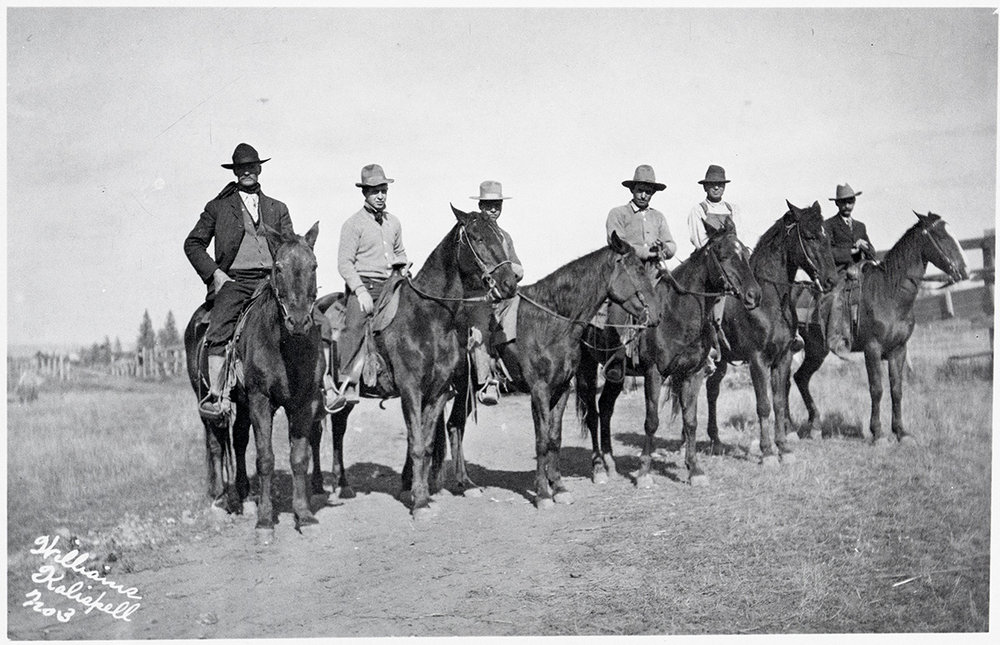

His social life was no less active than it had been in Helena, with regular visits to nearby towns, often on horseback. In April 1892 Charles fractured his collarbone falling from a horse near Kalispell, but he got right back on the horse, continuing his jaunts with friends to Columbia Falls and Helena and all around the Flathead Valley. In July he and three friends visited the upper end of the valley on horseback.

Charles was not lacking for company, and regularly attended balls, parties, and visits with friends that were covered by newspapers all over Montana. The Columbian newspaper in nearby Columbia Falls particularly covered his 1892 comings and goings with breathless excitement. There was a pink domino party in Columbia Falls, attended by 75 of the region’s society folks. Dancing began in the evening, “masks were dropped at 10:30” and dancing continued until 2 a.m. with a break for supper at midnight at the Columbia hotel. The “evening was made memorable by the presences of twenty-eight guests from the city of Kalispell who came up on a special train over the Great Northern.”27 One of them was Charles.

In June, “C.D. McCreary, one of the most popular young society men of Kalispell, paid Columbia Falls a visit….”28 In July he visited Columbia Falls on horseback with two friends from Kalispell. And in September he rode from Kalispell to Columbia Falls to attend a ball at the Gaylord. Charles took part in a horseback party to Whitefish Lake with a group of around 15, where they enjoyed boat trips and hammocks before heading back to Columbia Falls.

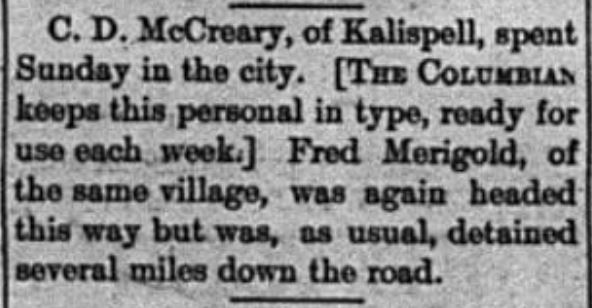

A week later, it was reported that Charles accompanied Mr. and Mrs. E.L. Harwood — who had thrown a dancing party at the West Hotel in Kalispell that Charles had a attended, and where many of the young men wore full evening dress — as far as Columbia Falls on their trip eastward, and then he stayed on and “Sundayed” there.30 In early October the Columbian printed the following social report, “C.D. McCreary, of Kalispell, spent Sunday in this city.” It then added, perhaps a little hopefully, “[Columbian keeps this personal in type, ready for use each week.]”31

In December 1892 Charles still held all of his positions in the local organizations he had helped found, and on the day after Christmas he went to “one of the most enjoyable parties of the season,” a gathering of twenty-two local bachelors, which was but a small fraction of those in Kalispell — most men in town were unmarried due to a dearth of single young ladies.32 The ones who had received gift boxes containing delicacies from home shared them with the rest, for an informal spread at the West Hotel. The gentlemen left the West Hotel and spent the rest of the evening serenading the streets of Kalispell, breaking up the party with a final rendition of “Good Night Ladies.”

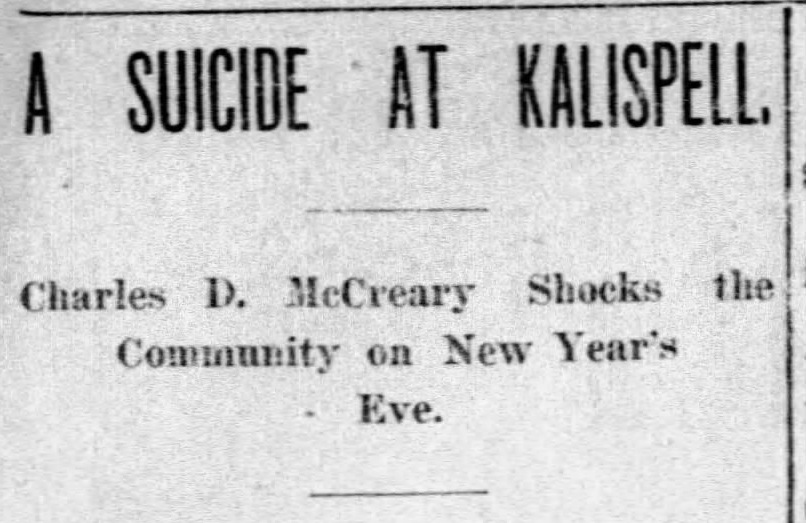

Five days later, at 4:30 in the afternoon on New Year’s Eve, Charles took his own life with a pistol.

The death of Charles McCreary

What could have driven such a popular and successful young man to suicide?

The various Montana newspapers offered some theories. “He could not conquer the liquor habit,” the Red Lodge Picket declared.34 “Despondency was the cause,” according to the Helena Independent-Record, which also called him “one of the most popular young men in the city.” 35

The Inter Lake gave the news several paragraphs. “The direct cause assigned for the rash act was a despondent disposition, at times, or melancholy,” it reported in an article entitled Charles D. McCreary Suicides. “Though he had his faults he also possessed those traits of character that beget the strongest ties of friendship among his associates, and to Charles D. McCreary he was [his own] worst enemy.”36

In all, seven newspapers reported on his death. But the Columbian, once Charles’ greatest cheerleader, remained silent and never mentioned him again.

The Kalispell Presbyterian church was packed on January 2, 1893, for Charles’ funeral. “His friends were countless and the shock of his sudden death “cast such a gloom over our city as to be almost visibly felt,” the Great Falls Tribune wrote, noting that the funeral attendance was very large and that “sorrow was shown in every face and tears in all eyes.”37

Demersville had nearly disappeared as residents abandoned the former boomtown for Kalispell, but the cemetery, Flathead County’s first, was still in use. Charles D. McCreary found his final resting place there.

At the time the cemetery kept no records, and only began recording burials six months later, and then rather carelessly. “We’ve had so many hands in the pot,” Clerk and Recorder Paula Robinson was quoted as saying in a 2013 Inter Lake article. “Lot sales have been kept track of haphazardly … It’s just a mess.” 39

Eventually Charles was recorded as having died in 1902, but it’s clear from the chronology of the record book that his entry was added, incorrectly, sometime after 1905, many years after his death. A 2013 article in the Flathead Beacon about the cemetery reported that many of the graves there were missing records and headstones. “Not only is the memory of these souls forgotten, but so is their history – the history of the Flathead Valley and beyond.”40

Meanwhile, in Maryland, Charles’ letters to his sister May had stopped. After some time a trunk of his belongings arrived with a letter stating that he was dead. Her grandson described it as an “unexplained mystery” that left May devastated.

Very rarely do the friends and family of those who take their own lives understand why. The reasons Charles committed suicide seem no more obvious now, 130 years later, than they did at the time. Was all of his socializing covering a deeper despondency? Or a drinking problem? Was he having financial or romantic problems? These are questions that no amount of research will probably ever be able to answer.

I have only included citations for images and direct quotes. There are more than 90 sources for this piece, most of them primary, and it would take up too much space to post them all! Each fact in this piece is meticulously sourced; if you are interested in where any of the information came from, please drop me a line and I’d be happy to share.

Photograph of Rebecca Norris Duer and William G. McCreary. Undated, circa 1861-1862. Privately held by Connie Haggard (Constance Miles Haggard), great-granddaughter of Rebecca Norris Duer and William G. McCreary. ↩

While one can appreciate William’s desire to keep his family business private, one can also resent the fact that he was trying to stop future historians from knowing too much, including his great-great-great- grandchildren, who are now combing through every insignificant detail of his life, hoping to understand more about it. ↩

US Army Signal Corps. Image of Widow’s Pension application number WC147297, Veteran William G. McCreary, Pensioner Rebecca N Duer McCreary, in “Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Widows and Other Veterans of the Army and Navy Who Served Mainly in the Civil War and the War With Spain, compiled 1861 – 1934” National Archives Catalog ID: 30023, Record Group 15, Roll WC147276-WC147302, National Archives, Washington, D.C.https://www.fold3.com/file/315309696: accessed 25 Jul 2021. ↩

US Army Signal Corps. Image of Widow’s Pension application number WC147297, Veteran William G. McCreary, Pensioner Rebecca N Duer McCreary, in “Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Widows and Other Veterans of the Army and Navy Who Served Mainly in the Civil War and the War With Spain, compiled 1861 – 1934” National Archives Catalog ID: 30023, Record Group 15, Roll WC147276-WC147302, National Archives, Washington, D.C.https://www.fold3.com/file/315309696: accessed 25 Jul 2021. ↩

Photograph of the second Charles Duer McCreary, with note identifying the subject, believed to have been written by May McCreary Jones. Undated, circa 1869. Privately held by Ron Seidlich, great-grandson of May McCreary Jones. ↩

“Interesting to the farmer boys and girls.” The Aegis and Intelligencer. Bel Air, Maryland. 20 August 1880. p. 2c. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

“Names of prominent men are on old deed from Fort Benton.” Great Falls Tribune, Montana. 5 June 1927. p. 3a. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 25 July 2021. ↩

Benton and Helena stage pulling out of Sun River Cross, 1885. 4×5 inch negative. Collection of C.E. Conrad. Montana Historical Society Research Center. https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/13091: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

“City and state.” The River Press, Fort Benton, Montana. 11 January 1893. p. 5a. https://www.newspaperarchive.com: accessed 21 April 2021. ↩

“Wilna items.” The Aegis and Intelligencer. Bel Air, Maryland. 18 December 1885. p. 2d. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 25 July 2021. ↩

“Bank of Northern Montana.” The River Press, Fort Benton, Montana Territory. 12 November 1884. p. 6c. ↩

“Montana’s Paris.” Farmland Enterprise, Farmland, Indiana. 5 October 1888. p. 8e. Quoting Edwards Roberts in Harper’s Magazine. https://newspaperarchive.com: accessed 12 July 2023. ↩

“Local notes.” The River Press, Fort Benton, Montana Territory. 6 October 1886. p. 6a. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 26 July 2021. ↩

“Local Notes.” The River Press, Fort Benton, Montana Territory. 6 February 1889. p. 6a. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 26 June 2021. ↩

Helena, Montana, Business Section. View of businesses and homes in Helena, Montana. Circa 1890. Unknown photographer. Photographic print on board mount. Montana Historical Society Research Center. https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/75885: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

“Statehood at last.” Helena Daily Herald, Montana. 8 November 1889. p. 8a. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 9 July 2023. ↩

Independence Now and Forever: Main Street in Helena, Montana. 4 July 1889. Unknown photographer. Photographic print on board mount. Montana Historical Society Research Center. https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/91728: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

“A Festal Day: Bishop Brondel’s Silver Jubilee.” Helena Weekly Herald, Montana. 19 December 1889. p. 5d. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 7 July 2021. ↩

Kalispell around the time of its incorporation in 1892. Photographer unknown. Collection of Museum at Center School, Kalispell, Montana. https://golocalflathead.com/2017/11/30/historic-downtown-kalispell-2: accessed 7 July 2023. ↩

“The short wild life of Demersville.” Tabish, Dyland. The Flathead Beacon, Montana. 19 May 2021. https://flatheadbeacon.com/2021/05/19/short-wild-life-demersville: accessed 9 July 2023. ↩

Klassen, Henry C. “The early growth of the Conrad banking enterprise in Montana, 1880-1914,” Great Plains Quarterly, volume 17, No. 1, pp 49-62 (1997). https://www.jstor.org/stable/23531948: accessed 7 July 2023. ↩

Bank, Conrad Bros. Bankers. 1891. Kalispell, Montana. Unknown photographer. Photographic print, postcard mount. Montana Historical Society Research Center. https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/75537: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

Stanford, Harry. “Kalispell in 1892 — A Lusty Infant.” In Elwood Henry, ed. Kalispell, Montana and The Upper Flathead Valley, pp.55-62. (Kalispell, Montana: Thomas Printing, Inc., 1989) https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/5595: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

Stanford, Harry. “Kalispell in 1892 — A Lusty Infant.” In Elwood Henry, ed. Kalispell, Montana and The Upper Flathead Valley, pp.55-62. (Kalispell, Montana: Thomas Printing, Inc., 1989) https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/5595: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

Twilight scene on the Flathead. View of saddled horses grazing among lines of Salish tipis on the Flathead Indian Reservation, Montana. Date and photographer unknown. Black and white photographic print. Montana Historical Society Research Center. https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/98250: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

Workers for Charles E. Conrad on horseback. Six unidentified men, wearing hats, sit on horses that are standing in a row. Kalispell, Montana. Date and photographer unknown. 4×5 inch negative. University of Montana Mansfield Library. https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/16267: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

“In pink dominoes.” The Columbian, Columbia Falls, Montana. 25 February 1892. p. 2a. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov: accessed 25 June 2021. ↩

“News of the week.” The Columbian, Columbia Falls, Montana. 30 June 1892. p. 2a. http://montananewspapers.org: accessed 24 June 2021. ↩

“C.D. McCreary, of Kalispell…” The Columbian, Columbia Falls, Montana. 6 October 1892. p. 2b. http://montananewspapers.org: accessed 25 June 2021. ↩

“News of the week.” The Columbian, Columbia Falls, Montana. 15 September 1892. p. 2a. http://montananewspapers.org: accessed 25 June 2021. ↩

“C.D. McCreary, of Kalispell…” The Columbian, Columbia Falls, Montana. 6 October 1892. p. 2b. http://montananewspapers.org: accessed 25 June 2021. ↩

“Holiday festivities.” The Kalispell Graphic, Montana. 28 December 1892. p. 3a. https://news.google.com/newspapers: accessed 2 March 2023. ↩

“A suicide at Kalispell. Charles D. McCreary shocks the community on New Year’s Eve.” Great Falls Tribune, Montana. 7 January 1893. p. 5a. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 27 June 2021. ↩

“County and State News.” Red Lodge Picket, Montana. 14 January 1893. p. 2c. https://www.newspaperarchive.com: accessed 17 April 2021. ↩

“Suicide at Kalispell.” The Helena Independent, Montana. 1 January 1893. p. 7c. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 27 June 2021. ↩

“Chas D. McCreary Suicides.” The Inter Lake, Kalispell, Montana. 6 January 1893. p. 3e. ↩

“A suicide at Kalispell. Charles D. McCreary shocks the community on New Year’s Eve.” Great Falls Tribune, Montana. 7 January 1893. p. 5a. https://www.newspapers.com: accessed 27 June 2021. ↩

Demersville Cemetery, Flathead County, Montana. 1996. Photographer Angie Clark. The MTGenWeb Project.https://flatheadgenweb.weebly.com/demersville-cemetery.html: accessed 8 July 2023. ↩

Hintze, Lynnette. “Work group sought for historic cemetery.” The Daily Inter Lake, Kalispell, Montana. 28 September 2013. https://dailyinterlake.com: accessed 7 July 2023. ↩

“The Demersville Cemetery.” Flathead Beacon, Kalispell, Montana. 17 September, 2013. https://flatheadbeacon.com: accessed 7 July 2023. ↩