Wondering how to start the process of using DNA research and genealogy to find your biological family, or help an adoptee do the same? Here are a few tips.

Get tested at both Ancestry and 23andMe. Both have big databases but you can’t compare your results to the people in their database unless you test with them directly. If you can only test with one, start with Ancestry because their database is larger and users there are more likely to have public family trees. But, if you are stumped, make sure to test with both companies.

Upload your DNA to MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA, and GEDMatch. All of these sites have different databases of people who have tested, and you don’t know which one your undiscovered half-sister is on. You’ll need to download your results from Ancestry or 23andMe first.

If you are only trying to discover the identity of one parent, it will save a lot of time and work if you can have the known parent do a DNA test as well. This will allow you to eliminate matches who are related through the known parent from the pool that needs to be examined.

For the most part, you can ignore the ethnicity estimates. These are just the DNA companies’ best guesses and are pretty meaningless. If Ancestry says you’re 20% Italian and MyHeritage says you’re not Italian at all, ignore it. The only thing that matters are your actual DNA matches, which are not estimates.

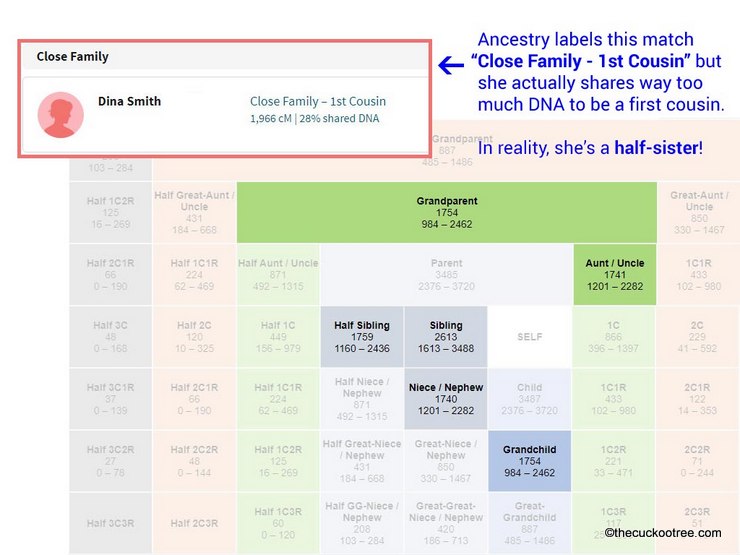

You can also ignore the relationship estimates, because they are very often not correct. For example, Ancestry will suggest “close family to 1st cousin” for half-siblings. Instead, use this great tool at DNA painter to see what possible relationships you might have with someone based on how many cMs you share.

Try the Leeds Method. This is a pretty easy process that can help divide up the matches into four family lines that should match each of the four grandparents. It often doesn’t work perfectly because success entirely depends on having DNA results from enough family members from each line, and it’s clear that some families and some populations just aren’t as into DNA testing as others. It’s also less effective on endogamous populations (such as Jews). But when it works, it works really well. In any case, it’s a good place to start and can help sort the adoptees’ matches into family “buckets.”

Create one big family tree with mini-trees for every person on your match list. Some people like to create multiple trees, but I find it’s easiest to have lots of little trees within the same file, and then linking them together when I get enough information. Depending on how closely related your top matches are to you, you’ll be able to narrow this down quickly to one family for each biological parent. If you only have 3rd and 4th cousin matches, it will require building out bigger trees. The goal is to try and see where all of your matches intersect, which will allow you to find your most recent common ancestor. This can end up being a big project, because it can require building trees for each match for several generations. But eventually all of the matches will connect with each other into two big trees — one will end up being the biological father’s family and the other will be the family of the biological mother, and the person who took the DNA test is the link that connects the two trees.

To build family trees for people you don’t know, start with the matches who already have public family trees. Then you’ll need to put your gumshoe hat on and start searching. Checking newspaper archive sites (such as newspapers.com and newspaperarchive.com) for obituaries is a great way to build family trees. Obituaries often list the names of parents, children, spouses, and more. Google searches and Facebook research can also turn up invaluable leads.

Be cautious about sending messages to your matches. When you get your results your first instinct may be to immediately contact all your closest matches and see if they know how you are related. Unfortunately, in many cases the matches will react by vanishing off of the DNA site and taking their family tree with them. Before you message any close matches, take screenshots of their profile, their family tree, and your shared matches. I wait until I’ve already built out the family trees and know how a new match is probably related before I contact them, but then I send fairly ambiguous messages. Some people might be shocked to find out they have a previously unknown close relative (which suggests infidelity in their family) and not want to deal with it. The same people might reply to messages asking for more general family information, or for their help in figuring out how you are related. Sometimes it’s best to let the match reach their own conclusion rather than telling them directly how you are related.

Once you’ve done all of the above steps, if you still can’t figure it out, head to DNA Detectives or DNA Detectives for the Donor Conceived on Facebook and ask for a more experienced researcher to review your work. Figuring this out can be complicated the first time you do it, but people who have done this before can help. If you have not tested with both Ancestry and 23andMe and do not have close DNA matches, they will probably ask you to test with both first.

Some cases can be too difficult to figure out if not enough relatives have already tested, but be patient. In a few months another match may show up on your list and everything will become clear. I’ve had cases I’ve been able to figure out in less than an hour, and have another one that is a year old and still going strong. So don’t give up hope and keep checking your match lists for new clues.

Thank you for this – you have confirmed my approach. I have matched 2 close relatives on 23&me for years, both with the same surname but flimsy matches at <3%. I tested recently on ancestry and have much closer matches, and more numerous – plus it seems like lots of high schoolers build out a small tree as an assignment and then forget about it – which is actually super helpful. I matched 2 siblings at 15% and 11% (which is just about close enough for an invite to Christmas dinner), and it took me about a day to identify my maternal parent – me being their half uncle. I have other shared matches on what I believe is the paternal side but not as strong – still in the 5% – 9% range though. I've built multiple trees and identified several shared ancestors, and think I'm at least homing in on a surname – I have 2 matches with shared ancestors and I'm trying to find a 3rd vector to those matches. People in the 1800's and early 1900's had so many kids it's tedious to test every hypothesis. I haven't reached out to any of my matches as you mentioned as well – it seems awkward to me, but I've made it clear in my profile that I'm open to connect. Not all the paternal puzzle pieces have clicked together yet, but I'm pretty confident I'll sort it out soon…

I struggle a little with this, because it feels creepy to be researching family trees that I have no personal relationship with. Ultimately, I feel like I have a right to my genetic heritage, and I never thought that I would have this. Science is awesome…

It can definitely be hard to be sure if you don’t reach out and get confirmation — I helped an older adoptee (who was a distant 4th cousin to me) narrow down his mother to one of several sisters. When we eventually reached out to the family, they were very welcoming and knew exactly which sister it was, which cleared it up immediately. But in other cases I’ve worked on, the family was very unwilling to consider the possibility. Good luck with your search, it sounds like you are on the right track!