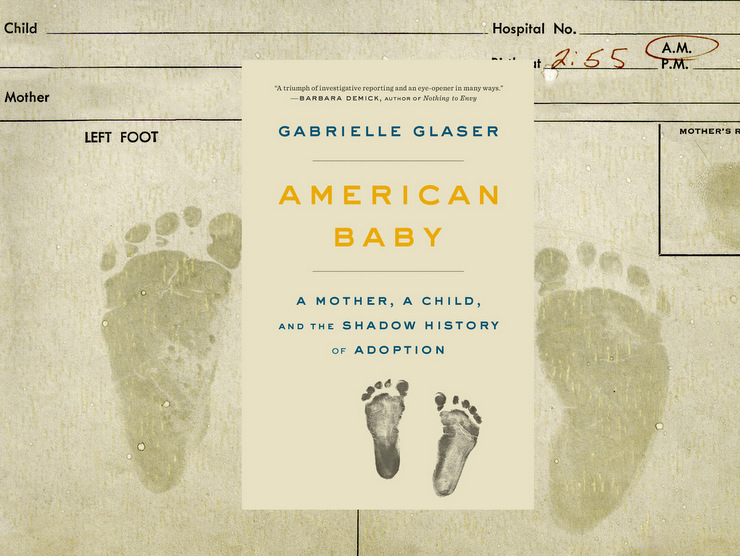

Like most genealogists who have taken a DNA test or three, I’ve come across several adoptees in my DNA match list. I was intensely curious about where these people fit in my family tree, but I had never given much thought to the process behind these adoptions, or known that babies could be taken from unwilling mothers who desperately wanted to keep them. Reading journalist Gabrielle Glaser’s compelling new book, American Baby: A Mother, a Child, and the Shadow History of Adoption, changed the way I look at adoption research.

American Baby tells the story of Margaret Erle, a teenager from a Jewish immigrant family in New York, who became pregnant in the 1960s when she was 16 years old, the result of her first sexual encounter. Margaret was a high-achieving student who was determined to keep her baby, but her mother and Louise Wise Services, the now-infamous Jewish adoption agency, were even more determined to make sure she didn’t. Margaret and the baby’s father, George Katz, overcame numerous obstacles to marry, but the baby was nevertheless given to another family. The story of how this happened is both horrifying and heartbreaking.

Glaser places the tragedy of Margaret and her baby in the larger context of how American adoptions skyrocketed during the Baby Boom era. There were 2.7 million adoptions between 1944 and 1974, a period known as the “baby scoop,” and that number doesn’t include private, gray- and black-market adoptions, which could account for a million more. Glaser explains that “in previous generations, young, unwed couples who found themselves with unexpected pregnancies married quickly and kept their babies.” But in the prosperous postwar era, families had higher aspirations for their children, and “these surprise pregnancies were an obstacle to a better life that needed to ‘go away.’” Families who were unable to conceive and longed to join the baby boom seemed the obvious solution.

On paper it seems to make sense to match the babies of unmarried teens with childless, unmarried couples who could give them a better life. But the stories that Glaser tells in American Baby, about the way adoption agencies lied to both mothers and prospective families, are shocking. One, in particular, still keeps me up a night. And they weren’t just lied to; the way these agencies treated unwed mothers was shameful, slamming doors in their faces literally and figuratively anytime they inquired about their children.

I thought I understood adoptions from this era, having helped research quite a few adoption cases from this period. I had heard many times that the mother “didn’t want to give up the baby, but she had to.” Until reading Glaser’s book I didn’t realize how often “had to” was literally true, nor did I understand the terrible pressure that was applied by both society and their own families to girls and women to make them give up their babies, even when they desperately wanted to keep them. Margaret, for example, was advised that she could be institutionalized in juvenile prison if she did not agree to sign the forms terminating her parental rights. It was not an idle threat. At the time, girls could be committed to reformatories for “deviant” behavior, which could mean anything from disobedience to “moral depravity,” including sex outside of marriage.

Margaret Erle went on to have a long, loving marriage and three more children with George Katz. Although her first son had a perfectly nice adopted family, it’s hard to argue that putting him out to be adopted gave him a better life than he would have had if he’d been allowed to stay with his birth parents, who by all accounts gave their other three children a happy, suburban childhood — the exact kind that adoptions were supposed to provide.

It is not a spoiler — it’s how the book opens — to reveal that eventually Margaret gets to meet her son as an adult, after she finds him through DNA testing and good old-fashioned genealogical research. I’m not ashamed to admit that I cried big, loud tears first when Margaret had her baby taken away and then again when she found him decades later.

American Baby is a revealing read for anyone who does DNA research, because if you haven’t been contacted by an adoptee yet, you will be sooner or later. For me, at least, this book was eye-opening about the assumptions I hadn’t realized I’d been making when acting as a “search angel” for adoptees. If children were given up willingly, it seems more likely that their biological parents might not want to be found. But if many babies were, in fact, adopted out against the birth mother’s will, that changes the picture dramatically. In Margaret’s case, she searched for her son for decades, always hoping to eventually find him.

Perhaps many others are doing the same. The genealogists who help them would benefit from reading American Baby: A Mother, a Child, and the Shadow History of Adoption to feel the emotional weight of their experiences. I had always believed that search angel research was healing for the child, but now I understand that in so many cases, it has the potential to be healing for the biological mother as well.

Interested in using DNA research to find an adoptee’s biological family? Find some pointers here.